Editorial

Volume 3 Issue 2 - 2019

Relational Treatment

Specialist in Family and Community Medicine. Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia. Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain

*Corresponding Author: Jose Luis Turabian, Specialist in Family and Community Medicine. Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia. Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain.

Received: February 23, 2019; Published: March 02, 2019

Keyword: General Practice; Family Practice; Healing; Therapeutics; Therapy; Physician-Patient Relations; Clinical competence; Systems Oriented Approach

Any knowledge requires contextualization. It is known that water boils at 100 degrees Celsius, but almost never does it at the same temperature. The scientific principle must be contextualized. But, what does the context consist of? For contextualization we must add dimensions that are not well contained in scientific discourse. One of these is the "relational dimension": things happen in the sphere of interaction between people.

It must be remembered that individual illness depends on relationships and in turn produces consequences in the relationships social, cultural, economic, environmental and political where it takes place. Therefore, the clinical activity of the general practitioner (GP) should always have a relational dimension even if you work with individuals or patients, who at first glance seem to be "alone". The patients are in relational contexts (families, social groups, neighbourhoods) and immersed in social networks that suppose resources, influences and connections [1,2].

Disease is expressed or experienced in the relational situations of the patient's daily life: work relationships, family relationships, etc. If the symptoms can not be contained within a certain relational situation by using certain resources (modifying schedules, postures, exercises, spaces, etc.), there is a certain rupture or dysfunction of their normal relational matrix, and the person has to leave or modify certain situations or relationships (rest, go to the bathroom, take pills, etc.); it is here that we can say that the disease is born. Illness is a relational concept. It is related to contexts; appears between the person and their relationships with contexts; it does not exist isolated from relationships [3-5].

The experience of people about themselves, with their meanings, dignity, power to act and relate to others, occurs within the matrix of social relationships. The properties of these matrices of relationships can both facilitate human interaction, connections, development and respect, or on the contrary, alienation, disconnection, rupture. Within the matrix of relationships is where people interact, participate, develop, solve problems, and give meaning to their world and themselves.

The relational contextualization of health problems allows a better clinical vision; thus, even in disorders in which the evidence of a biological component is indisputable, knowledge of the patient's relational matrix can allow us to know the evidence that this problem is maintained and remains more serious through its inclusion within the dysfunctional interpersonal circuits (family, group, and community). This emphasizes that the place of the pathology to take into consideration, in fact, is not the biological, not only the psychological, nor can the individual be considered as an isolated unit, but rather the individual is a component of the relational system in which he is inserted. Same groups of health problems where relational factors have traditionally been taken into account are cardiovascular, digestive, and respiratory diseases such as bronchial asthma, not counting mental health disorders, neurological ones, such as headaches, dementia, etc., in addition to pain, among others.

But in practice, however, these considerations are not taken into account. Although this forgetfulness could be "forgiven" to the "specialist" professionals who work with "body parts" (cardiologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists, etc.), the GP that works in an integral way can not be forgiven. Consequently, the GP must learn to know and handle the "relational dimension", where are the subjective experiences and latent motives of the health problems of their patients. Going through this relational dimension as blind to its existence, through a medical model that explicitly directs its attention away from it, causes many healing possibilities to be lost [6].

Disease can threaten, deform or break the patient's sense of connection with others or with the world. It can interfere with your safety; challenge your sense of control over your destiny. Pain, loss of function and other types of problems decrease the chances of contact, increasing the feeling of isolation in daily life. A feeling of connection with the doctor, of being deeply listened to and understood, reduces this feeling of being isolated and diminishes despair. This sense of connection is therapeutic, and it is in the essence of the doctor-patient relationship in general medicine [7,8].

It is possible to observe examples of relational treatments in health problems where there is a certain alteration of human behaviour. Thus, we must bear in mind that human behaviours are not mechanistic: fixed patterns of passive reaction to external stimuli. On the contrary, any behaviour is the result of coordination, learning, and adjustment of multiple causes and their results or changes.

For example, alcoholism (also smoking, diet, etc.), is a disease in which the patient shows a pattern of addiction associated with a recurrent compulsion (the alcoholic may realize the damage of uncontrollable alcoholism, but continues to drink). It is usually considered to be a psychological problem: alcohol abuse is a symptom of a problem in the person. Addiction is the result of a simple interaction between the alcoholic person and the bottle (FIGURE 1). The alcoholic has the need to control the obsessive need for the bottle. So, in this in this theoretical framework, the "cure" is achieved by aversive therapy, and in general with psychotropic drugs that modify brain neurotransmitters and finally the behaviour.

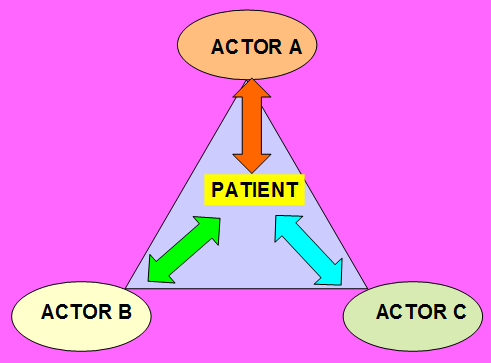

But, the alternative view of general medicine is that addiction is a problem due to alterations in human relationships. Alcoholism is the symptom of an error in the order of relations between the addict and his social world (his matrix of relationships) (FIGURE 2). The "cure" is in learning how to change the patterns of relational experiences. It is necessary to reorganize the "I" of the alcoholic on many levels, and he has to come to recognize that there is a multidimensional phenomenon. The GP and the patient have to accept that their own position is one more part of a larger situation. As some aphorisms say: "The tiger is only a part of the forest"; "An actor is only part of the play represented."

Therefore, the evolution of the disease (change, learning, healing, adaptation, etc.) in a living organism (a person, a patient) always concerns the individual plus his relational matrix. "Being" means "being related", and "being related" means building or modifying those relationships.

The illness in all cases, but especially when psychosocial factors predominate - for example, in mental illness (but, when there are no psychosocial factors in diseases?) is an alteration or dysfunction of communication relationships between actors (human beings), perceptions, and environments. In addition, when we believe that we intervene in isolated individuals, such as when treating an organic disease in an individual (pain, alcoholism, obesity, etc.), or dealing a mental disorder (that we define as an alteration of cerebral neurotransmitters) with drugs, we are never treating only to an individual, but the changes in that person (relief of pain, improvement of depression, abandonment of alcohol, or smoking, or changes in diet, learning disabilities, etc.) have repercussions on relationships with other individuals and these changes reverberate again about the patient, etc. Healing (treatment, GP intervention) becomes possible through the participation of the therapist in the matrix of communications and relationships with other people [9,10].

On the other hand, the style of the doctor can be crucial for the patient, since the majority of the patients look for a doctor who is not only competent but also has a professional style that fits him, especially if they are in crisis or they have a complicated and demanding chronic illness. The patient-physician connection reduces the feeling of dysfunction of the patient' relationship matrix. Thus, the personal style of the doctor can be important for the patient to learn to adapt to his illness and to reconnect the altered or broken connections [11].

This style is also important for the doctor, as it helps you connect with the patient who has gone to your office to be evaluated and possibly treat you. The doctor's feeling towards the patient may have an influence on future events in their relationships.

However, the GP must be realistic: getting into a patient's network of relationships and helping him recompose or change dysfunctional or broken relationships is difficult. The typical doctor-patient relationship is badly twinned because each of them considers the relationship as a confrontation. Although both have identical cultural profiles, only one of them is sick (patient) and the other (doctor) may not automatically understand what the disease means in their life, since the disease is not shared. The patient experiences symptoms that disrupt his life and cause anxiety, often because the nature and cause of the disease are unknown. The patient tells the story to the doctor, whose training, knowledge, objectivity and experience lead him to dissect and classify the components of the disease in order to establish a diagnosis. The focus of the patient is subjectivity, while the doctor focuses on the specific pathology of the lesion [12].

But, for the GP to make sound clinical decisions, it must use a set of tests, values, preferences and circumstances [13, 14]. Health is a property that emerges from the person understood as a complex life system. Thus, the whole can have properties that separate parts do not possess. So, it is unlikely that the biomedical treatment that typically addresses the individual's parts one by one, but not as a complete system, will obtain comprehensive results. The relational intervention includes the doctor-patient relationship, the conventional and unconventional multiple treatments (of alternative medicine), and the philosophical context of assistance as part of the intervention. The systemic results produce simultaneous interactive changes within the whole person [15].

In short, the GP must perform a "relational" approach to the patient's health problems, but at the same time, it must be realistic and understand the difficulties of this relational approach. In this difficult equilibrium, individual biomedical intervention often seems to be imposed, however, in contrast, the GP must not abandon this relational path and childishly accept the usual one-dimensional biologists intervention: it is easier, but less useful for the patient. As GPs we focus most of our efforts on treating people’s illnesses, but it is always helpful to consider the relational context in which their illnesses occur. The world that surrounds each one, the relationships of each one, are largely created by oneself because we are interpreting what surrounds us. Therefore, if the GP makes the patient vary the interpretation of what surrounds you, in a certain way, it is as if he varied the patient' relational environment.

References

- Turabian JL. “For Decision-Making in Family Medicine Context is the Final Arbiter”. Journal of General Practice 5 (2017): e117.

- Turabian JL. “Contextual treatment: a conceptualization and systematization from general medicine”. International Journal of Family & Community Medicine 2.3 (2018): 137-144.

- Gannik DE. “Situational disease”. Family Practice 12.2 (1995): 202-206.

- Turabian JL. “Ecological Implications of Decisions in the Individual Patient: Concentric Health Circles”. Chronicle of Medicine and Surgery 2.2 (2018): 104-109.

- Turabian JL. “Ecological analysis in general medicine”. Family medicine Care 1.1 (2018): 1-2.

- Turabian JL. “Interpretation of the Reasons for Consultation: Manifest and Latent Content. The Initiation of the Diagnostic Process in General Medicine”. Archives of Community and Family Medicine 2.1 (2019): 1-8.

- Turabian JL. “Doctor-Patient Relationships: A Puzzle of Fragmented Knowledge”. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care Open Access 3 (2019): 128.

- Turabian JL. “The enormous potential of the doctor-patient relationship”. Trends in General Practice 1 (2018).

- Hayes C., et al. “Understanding Chronic Pain in a Lifestyle Context: The Emergence of a Whole-Person Approach”. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 6.5 (2012): 421-428.

- Freedman R. “Coping, Resilience, and Outcome”. American Journal of Psychiatry 165.12 (2008): 1505-1506.

- Broyard A. “Intoxicated by my illness”. New York: Ballantine Books (1992).

- Toombs SK. “The meaning of illness: A phenomenological approach to the patient-physician relationship”. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 12.3 (1987): 219-240.

- Naylor CD. “Clinical decisions: from art to science and back again”. Lancet 358.9281 (2001): 523-524.

- Suárez F (2006) [Around the idea of "situation diagnosis"]. [Article in Spanish]. Area 3. NÚMERO ESPECIAL (ISSN 1886-6530) Congreso Internacional “Actualidad del Grupo Operativo” Madrid, 24 – 26 febrero 2006.

- Bell IR., et al. “Integrative Medicine and Systemic Outcomes Research. Issues in the Emergence of a New Model for Primary Health Care”. Archives of Internal Medicine 162.2 (2002):133-140.

Citation:

Jose Luis Turabian. “Relational Treatment”. Chronicle of Medicine and Surgery 3.2 (2019): 334-338.

Copyright: © 2019 Jose Luis Turabian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.